Brought to you from the Minnesota DNR.

Spiny waterflea (Bythotrephes longimanus)

Description

Appearance

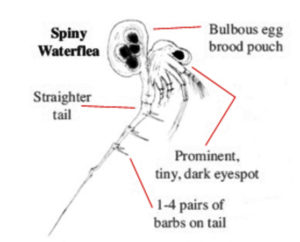

Spiny waterfleas are microscopic animals, also known as zooplankton, that live in open  water. Adults range from one-quarter to five-eighths inches long, and are opaque in color. They have a single long tail with one to four spines and have one large, distinctive blackeyespot. The spiny waterflea is often found on fishing line or other equipment in clumps that resemble a gelatinous blob with a texture of wet cotton.

water. Adults range from one-quarter to five-eighths inches long, and are opaque in color. They have a single long tail with one to four spines and have one large, distinctive blackeyespot. The spiny waterflea is often found on fishing line or other equipment in clumps that resemble a gelatinous blob with a texture of wet cotton.

Biology

The spiny waterflea is a predatory zooplankton that eats other zooplankton. They migrate into deeper waters during the day to hide from predators, and return to shallower water at night to find food. During the spring and summer, they reproduce by cloning. In the fall, or when conditions in the lake are cold or there is less food, they will reproduce sexually and produce tough eggs that are resistant to drying and freezing. Females carry their eggs and young on their back.

Origin and Spread

The spiny waterflea is native to Europe and Asia. The species was unintentionally introduced into the United States’ Great Lakes through the discharge of contaminated cargo ship ballast water. They were first discovered in Lake Ontario in 1982, and spread to Lake Superior by 1987. Refer to the infested waters list for current distribution.

Don’t be fooled by these look-alikes

Look-alikes:

- Fishhook waterflea (invasive)

- Leptodora (native)

- Chaoborus spp. (native)

Regulatory Classification

The spiny waterflea (Bythotrephes longimanus) is a regulated invasive species in Minnesota, which means it is legal to possess, sell, buy, and transport, but it may not be introduced into a free-living state, such as being released or planted in public waters.

Threat to Minnesota Waters

Invasive species cause recreational, economic and ecological damage—changing how residents and visitors use and enjoy Minnesota waters.

Spiny waterflea impacts:

- Clog eyelets of fishing rods and prevent fish from being landed.

- Prey on native zooplankton, including Daphnia, which are an important food source for native fishes. In some lakes, spiny waterfleas can cause the decline or elimination of some species of native zooplankton.

- They do not provide a good food source for native fishes, because their long tail and spines make them difficult to eat.

What you should do

People spread spiny waterfleas primarily through the movement of water-related equipment. The species collects in gelatinous blobs on fishing lines and downrigger cables. They can survive in water contained in bait buckets, live wells, bilge areas, ballast tanks and other water-containing devices. Adults and eggs, which may be hidden in mud and debris, can stick to anchors and ropes, as well as scuba, fishing, and hunting gear. Females can produce eggs which resist drying and freezing. Therefore, transfer of a single female could start a new population.

Whether or not a lake is listed as infested, Minnesota law requires water recreationists to:

- Clean watercraft of all aquatic plants and prohibited invasive species.

- Drain all water by removing drain plugs and keeping them out during transport.

- Dispose of unwanted bait in the trash.

- Dry docks, lifts, swim rafts and other equipment for at least 21 days before placing equipment into another water body.

Additional recommendation: Air dry for more than six hours to kill any spiny wateflea eggs.

Report new occurrences of spiny waterfleas to the DNR immediately by contacting your DNR Invasive Species Specialist or log in and submit a report through EDDMapS Midwest.

Control Methods

There is no known effective population control for spiny waterflea in natural water bodies at this time.